Mistwalker

Memory is a tide; I am its undertow.

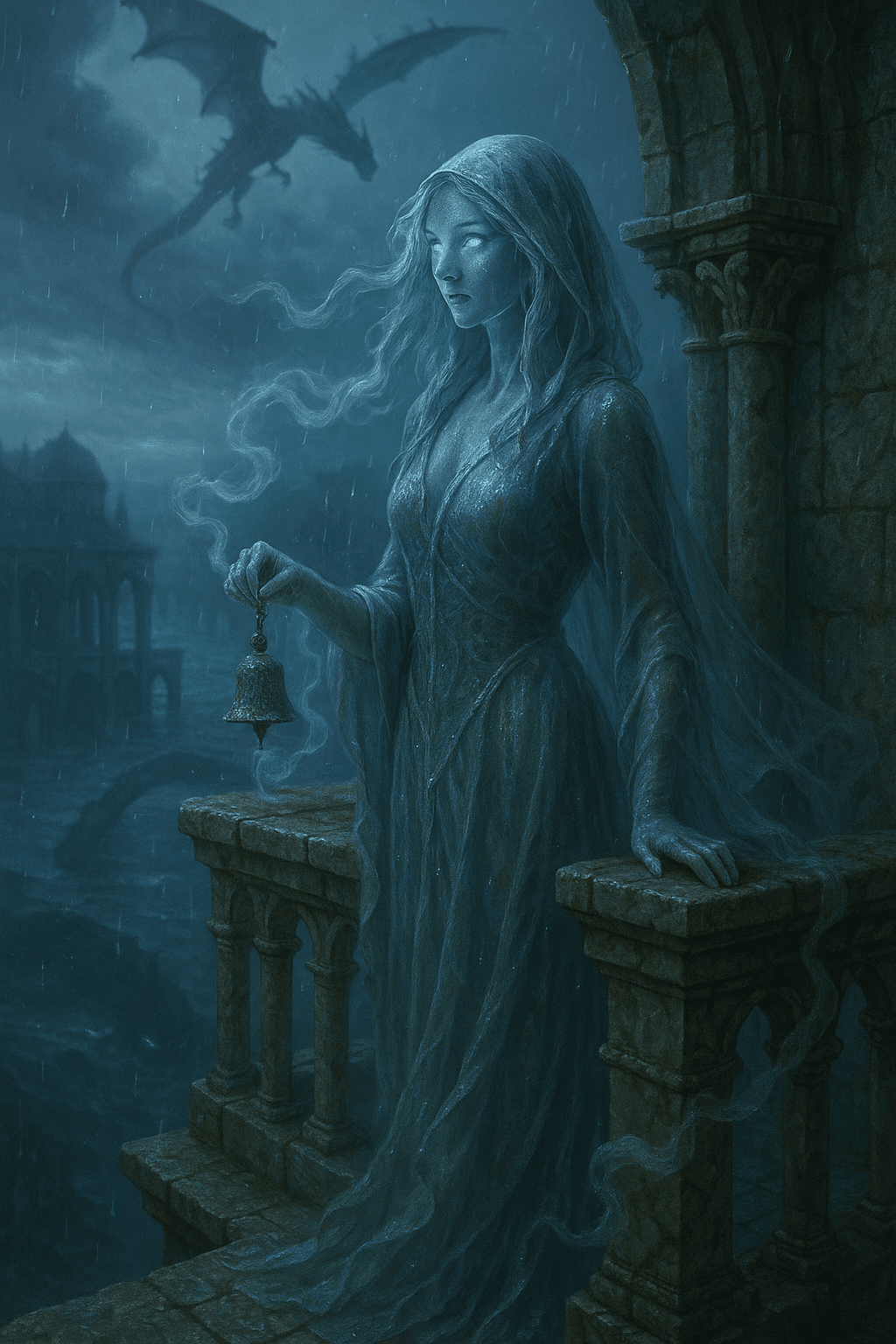

I speak of a figure whom the living meet first as weather—a coolness on the balcony stones of Elavorn’s Rest, a hush that presses grief into shape—before they realize the mist has a face. The elves call them Mistwalker, counselor of House Elavorn and guardian of the drowned history that still murmurs beneath Vaelorien’s terraces. Some say Mistwalker remembers the hour the sea came in; others say memory made them after, a spirit woven from all the names the waves could not keep. Both stories fit the way they stand: half in this world, half in the glimmer below.

Echoes.

In the age when the Deep Chime stirs and pilgrims return to ruined courts, Mistwalker moves like a lantern through fog—never blinding, always enough. Tidecaller Aeliryn trusts that light. The Tidecaller seeks unity between the living and the Drowned Spirits; Mistwalker makes that hope practical. They walk the tide-stairs at blue hour, listening to the water’s grammar, and set ward-lines where memory grows dangerous: here, where a street still thinks it is a river; there, where a balcony expects a feast that will not come. They do not command the spirits so much as negotiate with them, offering new rituals in place of the old rehearsals of loss. A bell rung once for mourning becomes a bell rung thrice for witness. The difference matters. The dead settle.

Mist-Dragons coil overhead when Mistwalker consults. They lower their vaporous heads until the air drips with soft rain, and the Tidewyrms beneath the glassy water give slow-turning approval. The dragons recognize in the counselor a kinship: protectors bound not to walls but to remembrances. When raiders slip through reefs to pry jeweled script from temple doors, Mistwalker steps out across the water on a path only they can see and speaks a word that buckles reflection. The intruders stagger, seeing themselves as the city once did—guests, not thieves—and more than one leaves empty-handed and bewildered, shame cooling their brazier-bright greed.

Politics has its own reefs. Seren Delsaar, the Restorationist, dreams of hoisting whole districts from the sea on chains of will and song. Mistwalker listens to the plan without interruption, then asks, gently, the questions that cut: Who will you wake that does not wish waking? Which banquet will you set when the guests have all become tide? What cost will you charge to those who cannot pay? It is not obstruction; it is stewardship. Even Seren, restless as a storm front, learns to speak of scaffolds and rites rather than miracles. The elves who serve the house call this the Mistwalk: the act of escorting a dangerous hope through fog until it chooses ground.

Their counterpart is Nymrielle, another spirit bound to counsel and omen. Together they tend the ledger of echoes—an archive of songs, scents, and names that survive in the coral libraries beneath the streets. When the Deep Chime trembles through the archipelago, the two spirits stand on opposite ends of a drowned avenue and hum a low harmonizing tone. Echo Serpents rise like silver script from the water, braid between them, and then dive, carrying the pair’s questions into the slow mathematics of the sea. Answers return as patterns in rain, as a gull’s turning, as a child’s dream of dry shoes found where none should be. Mistwalker writes those answers in salt-resistant ink along the inner rails of the Tidecaller’s balcony so the wind must read them before it moves on.

There is mercy in them, but not indulgence. Mistwalker has banished memory-harvesters from the reefs with a gesture that turned their lanternlight to darkness. They have stood beside Aeliryn in counsel with Itharûn envoys and, with a tilt of the head, asked the one question that makes martial courtesy become honest alliance: “Will you remember us when you do not need us?” The Wardens promised, and the promise held long enough to matter. When whispers from Duskfall carried dream-snares into the spired courts, Mistwalker salted the thresholds with a line so thin it could only be seen by those who had recently wept. The snares unraveled there, embarrassed.

What are they when the city sleeps? A patient tide-librarian. They visit the balconies where Drowned Spirits gather to rehearse old festivals and teach the dead to leave empty chairs for the living. They help the very young—those born after the drowning—to place paper boats in shallow squares and push them out with two hands, telling each boat the name of a lost ancestor. “Memory,” Mistwalker whispers, “does not bind you; it buoys you.” The children believe. The boats float through alleys lit by bioluminescent algae until Tidewyrms pass beneath and tow them along like a fleet.

If there is an ending for spirits, Mistwalker does not seek it. They are content to be a shape the water chooses when guidance is needed. The living say that when they offer thanks, the fog around the counselor thickens briefly, as if the sea itself were nodding. When grief claws at the heart too fiercely, Mistwalker leads the mourners down a spiral stair to a place where the city sings in bubbles, and there—between breath and memory—the ache loosens enough to allow tomorrow.

In this age of Echoes, Vaelorien hopes toward the surface without betraying the depths. Mistwalker holds that balance, one hand in the Tidecaller’s, the other in the cold, steady grip of the past. If the Deep Chime ever peals clear enough to change the world, it will find them already listening.