The Archivian Museum of Lost Histories

Where marble halls conceal truths the world is not ready to see.

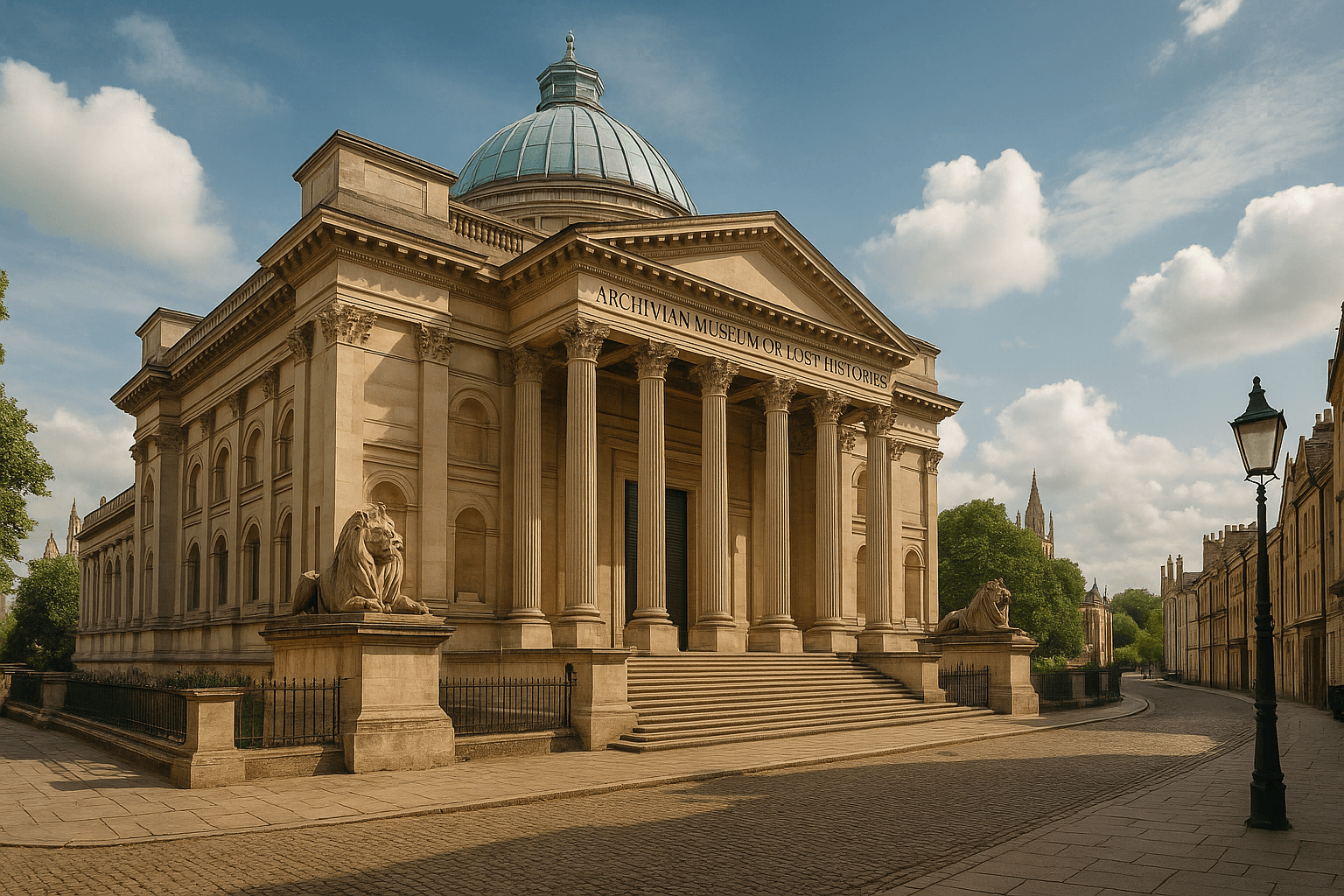

The Archivian Museum of Lost Histories rises just beyond Cambridge’s cloistered colleges, its marble pillars and copper roof catching the pale English light. To a casual passerby, it appears as yet another fine building folded into the city’s architectural rhythm, a cultural neighbor to the Fitzwilliam and countless chapels. But those who pause upon its steps often sense something different. The façade feels heavier, older, as if its foundation rests not only on stone but on centuries of secrets.

The Museum’s official history tells a comfortable tale. Founded in the late nineteenth century, it was described as a beacon of scholarship and preservation, a place where artifacts of the ancient world might be displayed to educate the public. Visitors wandering through its vast atrium today still find plaques and brochures repeating this line. They speak of donations, excavations, and the noble duty of learning. But this public face conceals a deeper, more complicated truth.

Behind the grandeur of its stained-glass skylights, the Museum exists to guard relics that others might prefer to see forgotten. The lion statues that flank the entrance are a fitting symbol. To most, they are carved guardians, decorative sentinels of stone. To a select few, they are known to contain hidden compartments whose mechanisms are understood only by the Director. Even the architecture of the building whispers of dual purposes. Corridors twist and double back, doors appear where none had been, and staircases seem to extend farther than the dimensions of the façade could possibly allow. Scholars who spend too long within often remark, in hushed tones, that the Museum feels larger on the inside than outside.

The public galleries remain a spectacle. Visitors stand awed by Egyptian tablets, Roman busts, maritime relics, and fossils of unimaginable age. School groups sketch the outlines of Greek amphorae while tourists marvel at star charts from forgotten centuries. Yet even here, illusion shapes the truth. Many of the most dazzling pieces are replicas, carefully crafted to satisfy the hunger for history while the originals rest elsewhere, under lock and ward, away from curious eyes. Staff explain little, and those who ask too many questions are redirected with a smile by Clara Niven, the ever-graceful receptionist who seems to know more than she says.

For the scholars who trade in whispers, the Museum’s true reputation is a subject of both fascination and unease. Some believe it houses manuscripts the University of Cambridge itself refuses to acknowledge, texts that could undo accepted historical timelines. Others claim its archives contain artifacts imbued with energies science has yet to classify. Rivals from London and beyond dismiss these stories as exaggeration, yet their envy is palpable, for the Museum has consistently acquired relics that more prestigious institutions could not secure.

To the city of Cambridge, the Museum remains an odd neighbor. By day, students sit on its steps with notebooks and sketchbooks, unaware of what lies within. By night, townsfolk cross the street to avoid its shadow, muttering that lights move behind its windows long after closing hours. The mist from the River Cam seems drawn to its façade, wrapping the building in shifting veils that hide and reveal it in turns.

The Archivian Museum is more than a collection of artifacts. It is a threshold, a custodian, a guardian of histories both remembered and deliberately forgotten. It stands not only as a monument to what humanity has discovered but as a warning about what should remain hidden until the world is prepared to face it.