The Field Network

Allies without banners, informants without loyalties — a shifting web of voices and shadows guiding the Museum’s hand in the world.

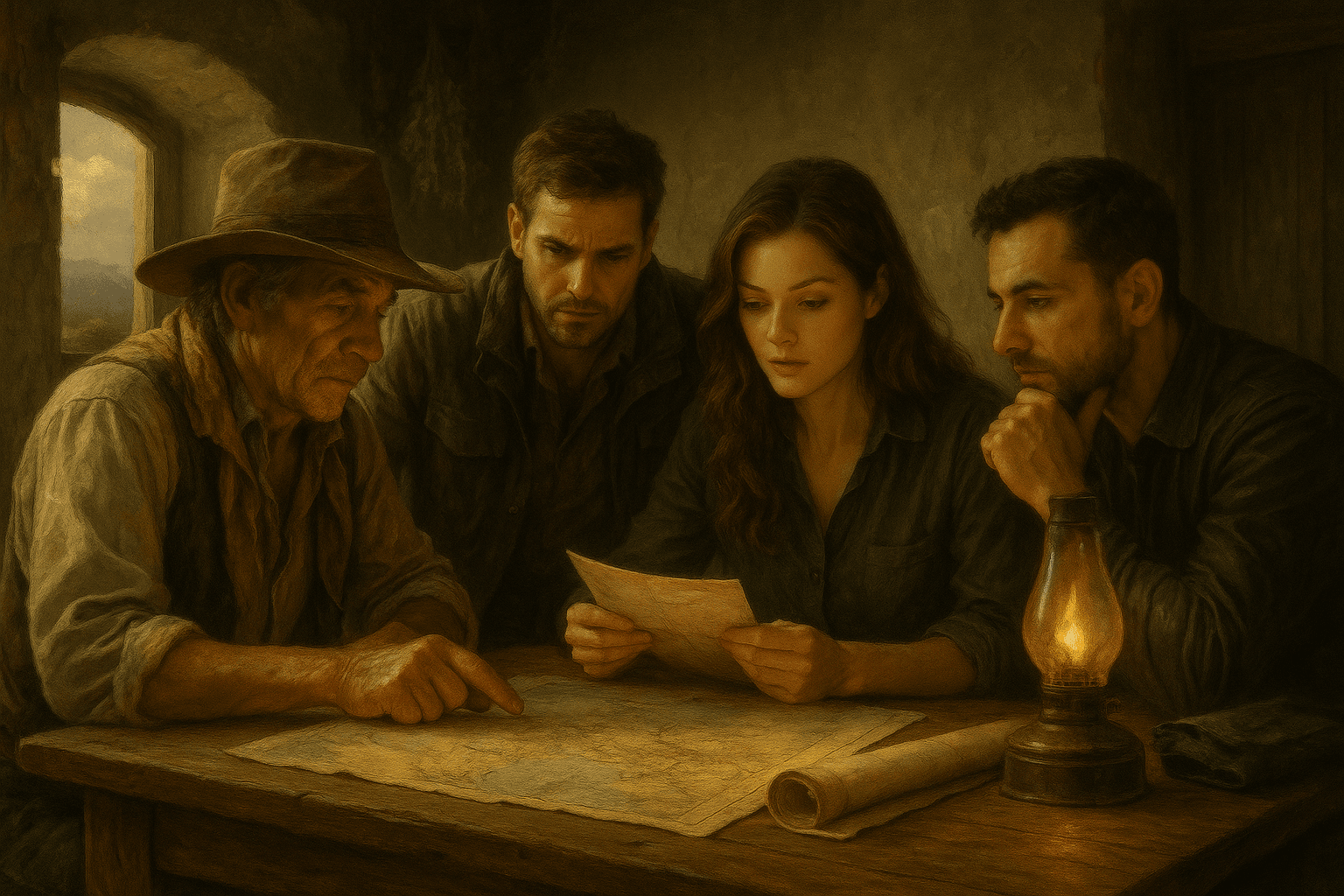

The Archivian Museum’s Field Core does not venture into the unknown alone. Behind every expedition lies a fragile web of contacts known simply as the Field Network — men and women scattered across borders, languages, and loyalties. They are not bound to the Museum by oath or contract. Instead, they trade in favors, survival, and opportunity. Their names rarely appear in reports, yet without them, half the Museum’s expeditions would never reach their destinations.

The Field Network is a patchwork of roles, each vital in its own way. Local guides are often the first point of contact. Generations tied to their landscapes give them an instinct no map can rival. They lead expeditions through rainforests, deserts, and labyrinthine ruins, pointing out dangers invisible to outsiders. Some guides view their work as survival, while others see it as a duty — custodians of hidden places who choose carefully who they allow to follow. But their loyalty is always conditional. If danger outweighs their pay, or if a rival whispers a better offer, they may vanish into the night, leaving expeditions stranded.

Historians and academics form another quiet backbone of the network. Their access to university libraries and local archives can unlock truths hidden behind bureaucratic doors. Some act out of passion, leaking manuscripts or oral traditions that institutions refuse to acknowledge. Others demand recognition, refusing to let their discoveries be swallowed under the Museum’s name. Their help is double-edged: they open doors, but their pride and resentments can drag the Museum into academic feuds as vicious as any battlefield.

Smugglers and fixers represent the murkier side of the network. When borders close and customs agents demand impossible paperwork, these operators slip relics through black market channels or provide forged permits that buy crucial hours. Some are disillusioned archaeologists who abandoned scholarship for profit. Others are career criminals who see expeditions as lucrative risks. The Museum knows better than to trust them fully, but in lands where laws clash with survival, smugglers are sometimes the only bridge forward. Their price is steep, and their allegiance fickle, yet many Field Core missions would have collapsed without their intervention.

Then there are the informants — nameless clerks in government offices, guards at restricted sites, researchers in rival institutions. They risk everything to pass along coded notes, excavation coordinates, or bureaucratic delays that give the Field Core an edge. Their motives are as varied as their identities: some act for money, others for revenge, others out of ideology. But all share one constant: the danger of exposure. A single slip can mean disappearance, imprisonment, or worse.

The Field Network itself is never centralized. Its members rarely know of each other’s existence, and many secretly serve multiple masters. Some whisper to rivals as easily as they whisper to the Museum, playing one side against another in hopes of survival. The Museum maintains a coded ledger of contacts hidden deep in the Whisper Archive, but even this record is incomplete. To rely on the network is to walk a knife’s edge — balancing gratitude, suspicion, and necessity.

In the shadows of expeditions, the Field Network thrives. They are the unsung allies, the necessary risks, and the invisible web connecting the Museum’s ambitions to the wider world. Their loyalties are as fluid as shifting sands, but without them, the Archivian Museum’s reach would be only a fraction of what it is today.