Public Galleries of the Archivian Museum

Where history wears a public mask, yet whispers of deeper truths behind the glass.

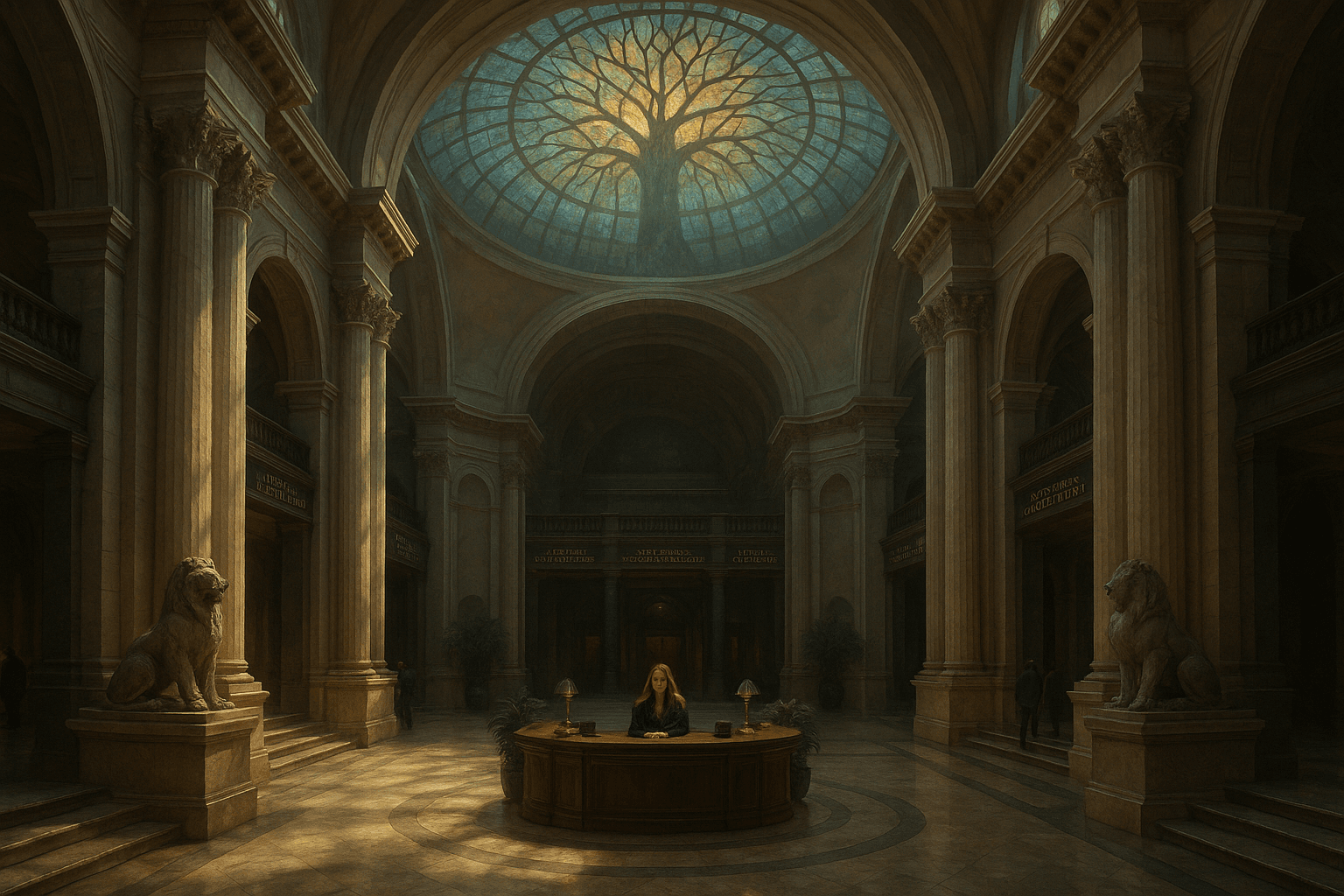

The public galleries of the Archivian Museum are the face it presents to the world. Beneath stained-glass domes and marble corridors, visitors step into spaces designed to impress, to instruct, and, perhaps most importantly, to distract. Each gallery carries its own character, a curated glimpse of history, yet always with the faintest sense that something lies just beyond reach.

The Hall of Antiquities is often the first stop. Visitors enter through towering bronze doors to find themselves surrounded by fragments of civilizations that shaped the foundations of the modern world. Egyptian stelae stand solemnly under soft light, their hieroglyphs casting shadows across stone walls. Nearby, Mesopotamian tablets, their wedge-like impressions etched with forgotten transactions and stories, sit under glass. Greek statues, weathered yet elegant, share space with Roman busts, their marble faces calm and imperious. Yet whispers abound among scholars that many of these pieces are finely crafted replicas. The true originals, some say, remain locked away in archives the public never sees, too volatile to display.

From the still solemnity of the ancients, visitors step into the Gallery of Maritime Wonders. Here the air seems different, tinged with salt and brine, though staff insist it is imagination. Glass cases hold the remains of sextants, salt-stained charts, and relics salvaged from shipwrecks long claimed by the sea. Lanterns hang from beams above, swaying gently as though stirred by unseen tides. The most haunting exhibit is a battered ship’s bell, its surface scarred by rust and storm, yet some visitors insist they have heard it toll faintly when no hand is near.

The Natural Curiosities Wing provides an entirely different spectacle. Fossils of creatures older than humanity line its echoing chambers, while gemstones and mineral samples glitter beneath glass. Taxidermy specimens, meticulously preserved, watch silently from their cases. Yet the deeper one walks into the wing, the stranger the displays become. Some fossils resist classification. A set of mineral samples hums faintly under certain lights, though scientists have yet to agree on an explanation. And in the deepest cases, pushed into shadows and rarely approached, lie objects excluded from official scientific record — things whose forms seem to straddle the line between biology and myth.

The quietest of the four is the Hall of Forgotten Cultures. Visitors enter to muted light and hushed voices, as if the air itself carries the grief of loss. Shards of pottery, fragments of woven fabric, ritual masks and tools from vanished societies rest under glass. Few linger long here. Tourists drift quickly past, unsettled by the silence that clings to the space. Scholars remain longer, scribbling notes about motifs that appear in cultures separated by oceans and centuries, connections that the official placards politely ignore. It is a hall not just of loss, but of unease, where the suggestion of forgotten truths presses close against the glass.

Together, these galleries form the Museum’s outward face, polished for the eyes of the public and presented as treasures for education and enlightenment. Yet every visitor senses, in some way, that what lies before them is only a fraction of the truth. The shadows between cases seem to guard more than they reveal. For the Archivian Museum of Lost Histories, even its public wings are not entirely what they seem.